By Jeff

Smith

Photography: Jeff Smith

Brought to you by Chevy

High Performance

|

| |

|

Where did the notion come from that adding more fuel to an

engine makes more horsepower? It’s one of those automotive

myths that clings to life even in the new millennium. It seems

just about every hot street car on the planet runs too rich

and could use a sharp tune-up. The latest victim in our quest

to rid the world of pig-rich hot rods was our pal Don

Swanson’s ’64 small-block El Camino.

A few months ago, CHP contributor Tim Moore put the tune-up

on Kevin Doyle’s mild 350-powered Camaro (“Attention to

Detail,” Dec. ’01). After we doubled the Camaro’s fuel mileage

while sharpening both the throttle response and tailpipe

emissions, it didn’t take long for his pal Don Swanson to ask

us to do the same with his car. Swanson’s El Camino presented

a much greater challenge since the small-block sported a lumpy

Isky 280/292 flat-tappet hydraulic cam that idled in neutral

with barely 8 inches of manifold vacuum. Compounding the

problem was a tight converter that pulled the engine down to

under 6 inches of vacuum in gear. The rest of the engine

included ported iron heads, headers, an Edelbrock Torker

single-plane intake manifold, and a modified Holley PN 80508

750-cfm vacuum-secondary carburetor.

Swanson complained that the small-block ran rich, fouled

plugs, and had a serious off-idle stumble that would sometimes

cause the engine to stumble under light acceleration from a

stop light. Swanson brought the El Camino over to Moore’s

shop, and we went to work. The first thing that Moore did was

check the idle emissions with his Sun HC/CO meter to establish

a baseline. The Sun machine tests four gases (HC, CO, CO2, and

O2) but we were most concerned with hydrocarbons (HC) and

carbon monoxide (CO). With the engine at operating

temperature, we measured a ridiculously rich HC idle of 1,500

parts per million (ppm) and a CO of 2.4 percent. CO percentage

can be used to indicate air/fuel ratio. The 2.4 percent figure

meant the engine was running at a reasonable 13.5:1 air/fuel

ratio. However, the HC level was especially high. Our goal was

to reduce the HC and CO to help the small-block run leaner and

crisper. We decided to shoot for reducing the HC down to

around 500-600 ppm, which would be a decent idle for a cam

this large.

First off, Moore noticed that Swanson’s motor was equipped

with suppression-type plug wires. While almost brand-new, the

wires measured 10,000 ohms of resistance. This is a little

high, so we replaced the suppression wires with a set of Crane

spiral-core FireWires that measured less than 500 ohms total.

Moore then fired the engine back up and checked the timing.

Using a new MSD self-powered timing light, the engine showed

14 degrees initial.

Moore also checked the idle mixture screws and found the

passenger-side screw was turned out only 1/8 turn while the

driver-side screw was over 1 turn out. Moore balanced the

idle-mixture screws at ½ turn each. If the idle-mixture screws

were turned out (richer) any more, the idle HC emissions went

dead rich. This indicated that the idle feed restrictors in

the carburetor were too large, allowing too little idle

mixture screw adjustment. |

| |

|

But before he could tackle that problem, we noticed that

after revving the engine a couple of times, the initial timing

was stuck at 34 degrees instead of the original 14. We pulled

the HEI distributor cap and discovered the small plastic

bushings that fit over the mechanical weight pivot pins had

failed, allowing the mechanical advance weights to stick.

Moore offered two new replacement bushings, and he cleaned and

lubricated the weights and reassembled the distributor.

With the timing stabilized, he could now address the rich

idle mixture. After pulling the carburetor and removing the

primary metering block, we discovered that the idle feed

restrictor for the carburetor had been drilled larger. The

standard idle feed restrictor size for most 750 cfm Holley

carburetors is around 0.034-0.035 inch. The restrictors in

this carb had been drilled to a larger 0.055 inch!

While this sounded bad, a typical big camshaft often

requires larger idle feed restrictors because the increased

overlap requires more fuel to keep the engine running. But we

also knew that the idle-mixture screws offered almost no

adjustment range. We used some 0.017-inch diameter electrical

wire strands and placed one inside each idle feed restrictor

in the metering block. This reduced the area of the

restrictor, which leaned the idle circuit.

We reinstalled the carb and allowed the motor to warm up.

Moore’s first step was to readjust the idle-mixture screws,

which now had a much greater range of adjustment than before.

However, a test drive revealed an off-idle hesitation that,

according to Swanson, had always been there but was now much

worse. He again removed the carburetor and discovered the next

common problem with big cams. Because of the long overlap and

reduced idle vacuum, the throttle blades had to be opened more

to allow enough air in for the engine to idle properly.

This larger throttle-blade opening uncovers a large portion

of the idle-transfer slot (see photo 9), which draws fuel from

the slot at idle. When the throttle is opened more, there is

insufficient fuel to compensate for the additional air

entering the engine. All of this occurs before the main

circuit tips in fuel from the boosters. The result is an

aggravating off-idle stumble. The cure required pulling off

the carburetor again.

We removed the baseplate from the carburetor and drilled

two 3/32-inch holes in the leading edge side of the primary

throttle blades. After cleaning all the metal chips from the

baseplate, we reinstalled the carburetor for another

testdrive. Drilling the holes allowed us to slightly close the

throttle blades, covering most of the idle transfer slot. A

quick test drive revealed that the off-idle stumble had

changed characteristics, but was still there! We were

frustrated. |

| |

|

By paying close attention to how the engine reacted, we

figured out what was happening. If Swanson eased the throttle

open, the carb worked fine. But if he hit part-throttle

quickly, the engine would hesitate and sometimes die

completely. This wasn’t a full-throttle stab, but more like a

1/8-throttle blip. After a few trips around the block, we

returned to the shop and discovered clearance between the

accelerator pump linkage and the pump arm at idle. This

allowed the throttle to move roughly 10 percent before the

accelerator pump squirted fuel into the primaries. The clue

was that Swanson’s engine would accelerate just fine when the

throttle was opened gently. We adjusted the accelerator-pump

arm to move in unison with the linkage and solved the problem.

Our next testdrive was much more rewarding—the engine

responded to throttle input crisply and without hesitation.

Swanson was thrilled.

Finally, we again plugged the El Camino into Moore’s HC/CO

machine and recorded the numbers. We didn’t gain a tremendous

reduction in HC/CO like we planned because the big cam just

wouldn’t allow the engine to idle with a leaner air/fuel

ratio. The best numbers we were able to achieve without

hurting driveability was a rather high 1,008 ppm HC and a CO

of 1.08 percent. What we did achieve was increased efficiency

in part-throttle operation and a crisper throttle that has

made Swanson’s El Camino a joy to drive. And that made all the

effort worthwhile. |

| |

| Article Sidebar: |

|

The Sniff Test |

CO to Air/Fuel Ratio Chart |

|

Old Wives’ Tale |

| |

| Article Source: |

| Crane Cams |

| Moore Automotive |

| |

Click here now to subscribe and get a

Free Trial Issue! Click here now to subscribe and get a

Free Trial Issue! |

| |

Click here for related Automotive

Books Click here for related Automotive

Books |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

Click

to enlarge photo

|

| |

|

|

Click

to enlarge photo

We started by pulling Swanson’s

immaculate ’64 El Camino into Moore’s shop and connecting the

HC/CO “sniffer” to read the exhaust emissions. This would give

us an accurate baseline. The carb is a Holley 750-cfm

vacuum-secondary piece with a Percy’s adjustable primary jet

plate installed. |

| |

|

|

Click

to enlarge photo

First we replaced the existing

suppression spark plug wires with a set of Crane Firewire

8.5mm spark plug wires. The original suppression wires checked

between 8,000 and 10,000 ohms of resistance. The Crane wires

came in between 200 and 300 ohms. With lower resistance, more

spark energy is delivered to the plugs, which makes the engine

run more efficiently. |

| |

|

|

Click

to enlarge photo

Next we tried turning the idle-

mixture screws but discovered an extremely small range of

adjustment. This indicated an overly large idle feed

restrictor so it was time to pull the carb apart.

|

| |

|

|

Click

to enlarge photo

Before we repaired the carb, we also

checked the timing with MSD’s new self-powered timing light,

which has an extremely bright strobe that is very easy to see.

We found 14 degrees initial timing the first time, but after a

couple of revs, this jumped to over 34 degrees. Clearly there

was something wrong inside the distributor.

|

| |

|

|

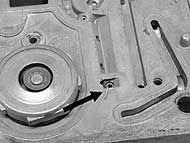

Click

to enlarge photo

We removed the cap and rotor and

discovered that the tiny plastic bushings that fit between the

mechanical-advance weights and the pins were wasted. Moore

replaced the bushings, and once the distributor was back

together, we reset the initial timing to 18 degrees with 36

degrees of total timing. |

| |

|

|

Click

to enlarge photo

We found a piece of 0.017-inch

electrical wire and cut two short lengths that we placed in

the idle feed restrictor to reduce the overall area from 0.55

inch to 0.038 inch. We hoped this would lean out the idle

circuit and reduce the HC emissions. |

| |

|

|

Click

to enlarge photo

The smaller idle feed restrictors

dropped the HC level, but a quick testdrive revealed a

now-worse off-idle stumble. We pulled the carb and found much

of the transfer slot uncovered. |

| |

|

|

Click

to enlarge photo

A cam with a ton of overlap will

require a larger throttle-blade opening where a large portion

of the idle transfer slot (arrow) is uncovered. This creates

an overly rich idle mixture and an off-idle stumble.

|

| |

|

|

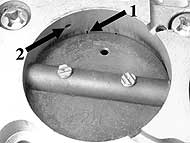

Click

to enlarge photo

After testing with another carburetor,

we drilled the two primary throttle blades with a 3/32-inch

drill bit. This bleeds more air into the manifold, allowing us

to close the throttle blades so that only a small portion of

the idle transfer slot is uncovered (arrow 1). Arrow 2 points

to the curb idle discharge hole. |

| |

|

|

Click

to enlarge photo

After resetting the idle mixture and

idle speed, the next test drive revealed improved throttle

response, but the engine still hesitated on light acceleration

off-idle. We readjusted the accelerator pump arm and the El

Camino instantly responded with its best throttle response to

date. |

| |

|

|

Click

to enlarge photo

1A clear indicator that the motor

suffers from massive overlap is the black carbon that has

coated the venturis of the carburetor. The carbon is the

exhaust soot reversion present in the intake manifold at low

engine speeds that contaminates the incoming charge. This is

why the engine requires so much fuel at idle.

|

| | |